Rethinking the US Naturalization Civics Test

Does Memorizing Facts Really Build Better Citizens?

If you read the headlines, you would think that making the naturalization test harder is a bold, patriotic move. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) just unveiled the latest overhaul of the US Naturalization Civics Test alongside the naturalization process. This comes as previous changes to the visa process were announced earlier this month. It has more questions to study, a longer exam, stricter scrutiny of “good moral character,” and even neighborhood investigations to confirm eligibility. These changes, officials claim, “restore integrity” and ensure only the “worthy” become Americans. The conventional wisdom? A more rigorous process yields more patriotic, assimilated new citizens.

This new civics test expands the pool from 100 to 128 questions, requires immigrants to answer more of them correctly (12 out of 20, up from 6 out of 10), and reintroduces a “stop-or-fail” rule mid-test. Answer 12 questions correctly: The officer will stop the test as soon as you give the 12th correct answer. You will have passed the civics portion of the naturalization test. Answer nine questions incorrectly, and the officer will stop the test once you accumulate nine incorrect answers. At that point, you will have failed the civics test. USCIS states that this will better assess an applicant’s understanding of U.S. history and government.

The USCIS claims these changes ensure only those who “fully embrace our values” can naturalize. But values aren’t demonstrated by naming the Chief Justice or reciting amendments. They’re shown by how people live, work, and contribute to their communities. If we genuinely care about “American values,” why not invest in robust integration programs like English classes, civic engagement, and mentorship instead of raising the bar on a memorization contest?

The Promise vs. The Reality

Civics tests, taken by naturalization applicants and, increasingly, by high school students, are often billed as a measure of civic knowledge, a litmus test for informed citizenship. But what do experts, researchers, and empirical studies actually tell us about their effectiveness? Does memorizing the “names of rivers” or “who was president in 1929” really make someone a better citizen? The evidence challenges conventional wisdom. You can view the 2019 version of the US Naturalization Civics Test here and see how many of these questions you can answer.

A major national survey by the Institute for Citizens & Scholars found that only 36% of Americans could pass a multiple-choice version of the citizenship test, with most unable to answer basic questions about U.S. history and government. Even more striking: only 27% of adults under 45 passed, and in most states, a majority failed. If “native” Americans can’t pass, why do we expect immigrants, often with less formal education and English fluency, to do so as a condition of citizenship?

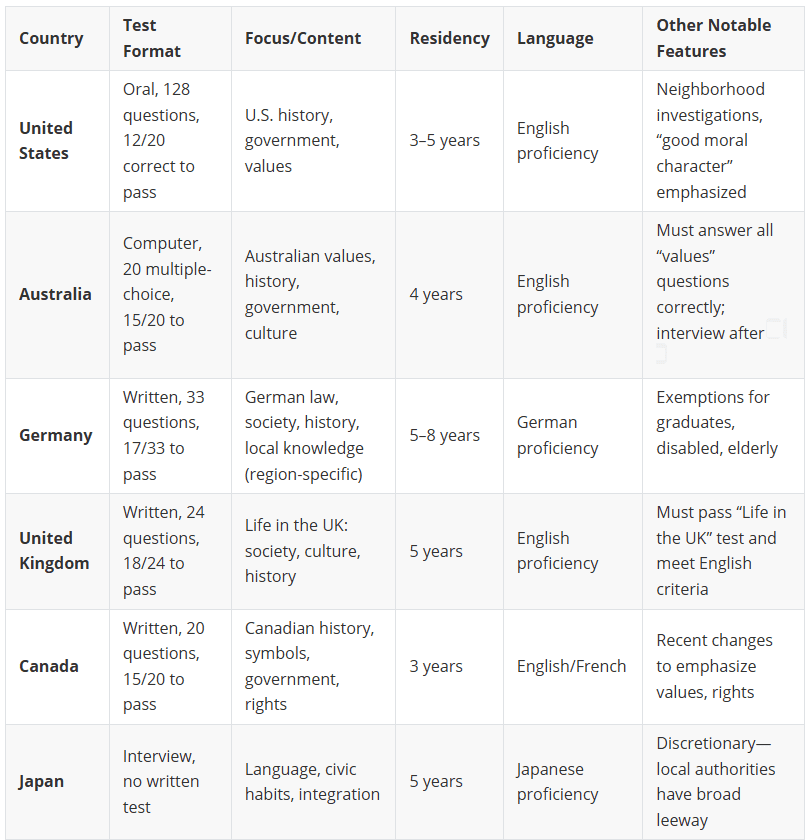

How Does the US Compare?

Countries around the world use diverse approaches to determine whether immigrants are ready to become citizens. While there’s no universal standard, the process typically combines residency, language mastery, civic knowledge, good character, and integration. Below is an evidence-based overview of how major democratic nations evaluate citizenship readiness.

What Would Actually Work?

Practical Civics Education: Teaching people how to participate. For example, how to vote, file taxes, advocate for community change, or even start a business would be far more helpful than memorizing trivia.

Skills, Not Facts: We’re learning something important from recent research: when it comes to civic education, teaching people how actually to participate in democracy matters more than drilling them on dates and names. When we give folks real-world tools, such as how to spot spin in the news or how to get involved in local government, they become true citizens, not just test-takers. It turns out, inspiring action beats memorizing facts any day.

Inclusive, Not Exclusive: A meaningful test of citizenship should focus on action, not just knowledge. Participation in community organizations, volunteer work, and active engagement with neighbors are all better predictors of someone’s commitment to American values than a high-stakes quiz.

Countries around the world use diverse approaches to determine whether immigrants are ready to become citizens. While there’s no universal standard, the process typically combines residency, language mastery, civic knowledge, good character, and integration. Memorizing facts for a test is not the same as becoming a citizen in practice. Countries that combine residency, language, and civic education with opportunities for real-world participation, such as volunteer work, community organizations, or local governance, tend to foster more integrated, engaged citizens.

What do you think

Should the US Naturalization Civics Test be reformed, or even replaced, to reflect what it means to be an engaged citizen in the 21st century? If the goal is to build cohesive, engaged societies, should countries move beyond rote civics tests and focus on demonstrable participation and integration in daily community life? Or is there still value in a formal, knowledge-based citizenship exam?

Additional Information